Detail Biography:

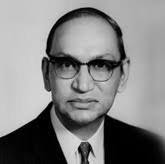

Name : Professor Raj Chandra Bose

Popularity : Mathematicians & Statisticians

Profession : Mathematics & Statistics

Published : Appellation : Bohm-Blatke Theory

Academic Qualification : M.A. PhD

Subject : Mathematics and Statistics

Educational institution :

M.A. (Pure Mathematics), Calcutta University-1927

M.A. (Applied Mathematics), Delhi University-1924

B.A. (Hons), Panjab University-1922

I.A. Panjab University-1919

Profession Institution :

Head of Mathematics, Indian Statistics Institute, Panjab-1932

Professor, Calcutta University, Calcutta, West Bengal, India-1940

Professor, Colorado State University-1947

Professor, Columbia University

Professor of Statistics, University of North Carolina-1949

Member of the American Academy of Sciences

Award : Keshalilal Mallik Gold Medal-1927

Father's Name : Prathap Chandra Bose

Father’s Profession: Government Physician

Mother's Name : Ushangenee Mitra

Siblings : Five (two brother & three sister)

Spouse Name : Sandhya Kumari Datta

Spouse Profession :

Children : Two daughters (Purabi Schur, Library of Congress and Sipra Bose Johnson, Professor of Anthropology)

Place of Birth : 19 June 1901 Hoshangabad, Madhya Pradesh, British-India

Place of Death : 31 October 1982 Fort Collins, Colorado, United State of America

Raj Chandra Bose: Universal Mathematician

H. Howard Frisinger and Indranath Sengupta

The first part of this article is a reprint of a forty-year-old article by Howard Frisinger that appeared in Gaṇita Bhāratī, about five years prior to the passing away of R.C. Bose. It is presented here with a supplementary essay by Indranath Sengupta, with the intention of providing a retrospective picture, embellished by illustrative images from his life.

The great Bengal renaissance took place during the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century, which marked the awakening of new thoughts in almost all spheres of intellectual pursuits. This period witnessed the birth of several great institutions like Hindoo College (later named as Presidency College, and now known as the Presidency University) in 1817, Bengal Engineering College (initially the Civil Engineering College) in 1856, Calcutta University in 1857, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) in 1876, department of Pure Mathematics in Calcutta University in 1912, Rajabazar Science college in Calcutta University in 1914, Indian Statistical Institute in 1931, to name a few. Calcutta (now Kolkata) was buzzing with the presence of great intellectuals and luminaries during this time. It was in the heart of such rich cultural ambience that the brilliant career of Raj Chandra Bose blossomed.

H. Howard Frisinger1

One of the results of the mathematical explosion of the 20th century has been the specialization of mathematical research, and the almost complete disappearance of the universal mathematician; those mathematicians who, like Carl Gauss and David Hilbert, were able to make significant contributions in several areas of mathematics. Such mathematicians are not completely extinct, however, as is exemplified by Raj Chandra Bose.

Raj was born in Hoshangabad on June 19, 1901, to Protap Chandra Bose, a military doctor, and Ushangini Mitra Bose, Protap’s second wife, his first having died childless. He spent his early life in Rohtak, some fourteen miles from Delhi. Protap was a strict disciplinarian and expected Raj to be at the top of his class in each subject. This, Raj was usually able to do. Once, in the eighth grade, however, Raj became ill while taking the mid-term examination in geography. This caused him to place only second in this class. Protap was very angry with his son’s performance and ordered him to learn Sohan Lal’s Geography of the World, (a 200-page book) by heart. By memorizing five pages per day, Raj was able to complete the task in less than two months, being able to repeat the entire book almost verbatim. It should be noted that both father and son had photographic memories, which certainly contributed to Raj’s later success as a mathematician. Raj recently demonstrated this exceptional gift by repeating to me a poem he learned some seventy years earlier in the third grade, starting on what page of the book the poem was located, and on what part of the page it started.

While Raj always enjoyed mathematics, and he recalls in grade nine becoming very interested in hyper-space geometry, he also enjoyed other areas of science. In addition, the study of Sanskrit literature gave Raj a great deal of pleasure. This study, which he continued throughout most of his life, has made him very proficient in Sanskrit literature. He can still repeat from memory substantial portions of the Kumārasambhava of Kalidasa.

Raj wanted to attend Punjab University, unfortunately, he fell sick with influenza at the time of the university’s matriculation examination, and consequently narrowly missed a university scholarship. Again he faced disappointing his father. As he could not afford to attend Punjab University without a scholarship, Raj instead entered the Hindu College at Delhi in April 1917.

Raj recalls that the first two years of college were some of the happiest times of his life. New horizons in mathematics and science were opening up to him. Not only these areas, but courses in Sanskrit literature, and Hindu religion and culture were a great joy to him. This idyllic part of Raj’s life came to a sudden end when in October 1918, his mother died, a victim of the great influenza epidemic which swept the world near the end of the first world war. The next seven years became a period of great trial and privation for Raj and his family.

Protap, who was in his early sixties, never fully recovered from his second wife’s death. Raj was able to provide his father with one last source of satisfaction by placing first in the Punjab University intermediate examination in 1919. However, shortly after this, Protap died of a stroke in January 1920.

By supplementing his scholarship income by tutoring, and later teaching in a high school, Raj was able to barely support his brother and two sisters and at the same time continue his education. He received a B.A. Hons. from Punjab University in 1922, an M.A. in applied mathematics from Delhi University in 1924, and an M.A. in Pure Mathematics from Calcutta University in 1927.

At Calcutta University, Raj came under the tutelage of Shyamadas Mukherjee, an excellent geometer. Mukherjee recognized the great potential of his student, and proceeded to help Raj in every way he could. Raj did not let his mentor down, standing first in the first class in the M.A. examination in Pure Mathematics in 1927, and also winning the University and the Keshalilal Mallik gold medals. In addition, Raj had published three papers in Hyperbolic Geometry and Four-dimensional Euclidean Geometry. The world of mathematics owes a great deal to Professor S. Mukherjee. He was a dedicated teacher, and it was from him that Raj learned the spirit of mathematical research. The kindness, encouragement, and stimulus Professor Mukherjee provided had, in Raj’s words, “a profound influence on my mathematical career’’.

The last third of 1923 was a pivotal period in Raj’s life. In September, Raj married Sandhya Kumari Datta. For nearly fifty years Sandy has been Raj’s constant companion and helper. He acknowledges that his very fruitful career has been due in large parts to Sandy’s faithful support.

In December, P.C. Mahalanobis, head of the Department of Physics at the Presidency College in Calcutta, offered Bose a part-time position as a research scholar in the newly founded Indian Statistical Institute. Thus began Bose’s education in statistics, a field in which he was to make notable contributions. During this period, Bose became acquainted with S.N. Roy, an applied mathematician. On Raj’s recommendation, Mahalanobis recruited Roy to the Institute. Roy became one of Bose’s closest friends, as well as one of his major collaborators.

Bose and Roy became the two chief mathematicians in the institute. Each summer Mahalanobis would select one statistical topic. It was the duty of Bose and Roy to master the topic, read all the important papers, and give lectures to the other junior members of the staff. Within a few years, the two chief mathematicians had become well-grounded in statistics. Realizing how good Bose and Roy were, Mahalanobis, in 1935, persuaded both to work full-time for the institute.

Statistical theory was in an interesting stage during the thirties. Methods had been devised for the situation when only a single character of some subject, like the yield of some crop, was under study. But methods were just in a developmental stage for the case when a subject was to be studied with respect to a number of characters. This subject is technically known as multivariate analysis. Mahalanobis was interested in the study of differences between various races, and for this purpose had devised a statistical measure called the Mahalanobis distance, or

In a series of papers, Bose and Roy developed methods of multivariate analysis. They developed what is called the distribution of

enabling valid conclusions to be drawn from samples about

Bose and Roy were part of a small group of researchers in multivariate statistical analysis, the others being Fisher and Hsu in England, and Hotelling in the United States. 1936 became another major turning point in the mathematical career of Raj Bose. The headship of the department of mathematics at Calcutta University became vacant with the death of Dr. Ganesh Prasad (1876–1935). This position was filled by Professor F.W. Levi who had fled Nazi Germany. Levi introduced some new areas of mathematics into the department, and Bose began to attend his seminars on algebra and geometry. Bose became especially interested in “finite fields’’ and “finite geometries’’. Levi was having trouble getting his mathematics colleagues at Calcutta interested in these “new’’ mathematical areas, and thus was impressed by Bose’s enthusiasm. They became good friends and Levi offered Bose a half-time position in the department of mathematics to teach “modern-algebra’’. To teach at the University of Calcutta had been one of Bose’s goals, and he accepted the half-time position.

During the same period in 1938, the silver jubilee of the Indian Science Congress was being celebrated. In connection with this jubilee, the then-leading statistician in the world, R.A. Fisher came to the institute as a visiting professor. At that time Fisher was interested in the study and construction of patterns called statistical designs, to be used in statistically controlled experiments. To Bose and the other members of the Institute, Fisher posed a series of problems arising out of this study. It occurred to Bose that he could successfully use the theory of finite fields and finite geometries, which he was then studying and teaching, as tools for the construction of designs. When he told this to Fisher, Fisher replied, “Young man, do you think it is really so?’’ Bose said “Let me try’’. Bose was able to solve one of Fisher’s problems during his stay at the Institute. When young Bose informed Fisher of his solution, Fisher was at first sceptical and made Bose present his solution at the end of one of the seminars Fisher was giving. Undaunted, Bose presented his solution and Fisher’s scepticism gave way to approbation. Fisher requested Bose to develop his methods systematically and send Fisher a paper which he promised to publish in the Annals of Eugenics of which Fisher was Editor. This resulting paper on “The construction of balanced incomplete designs’’ in 1939 has become a classic paper. Here, Bose was making a switch in his work towards design theory and other combinatory problems, and much of his efforts over the next ten years were devoted to this type of problems.

In 1940, Bose briefly left the Institute, and from January 1940 to June 1941, he became a lecturer in the department of mathematics at the University of Calcutta. In 1941, the University of Calcutta initiated a post-graduate department of statistics. S.N. Roy and Bose became the first lecturers in this new department. Mahalanobis became the honorary head, but most of the work of organizing the department and setting up courses of study fell on the shoulders of Bose. Bose had also rejoined the Institute in a part-time capacity.

One of Bose’s major contributions to mathematics and statistics came from his starting and leading students in their research. Many of these prodigies, such as K. Kishen, C.R. Rao, and S.N. Roy later became noted mathematicians and/or statisticians. C.R. Rao, in particular, who later became the director of the Indian Statistical Institute after Mahalanobis’ retirement, is now a world-famous statistician. Bose was not just a gifted researcher, but also an inspiring teacher.

In 1945, Mahalanobis relinquished the headship and Bose became the head of the Department of Statistics at Calcutta University. He also continued his part-time work at the Institute. Bose now determined to rectify a situation that otherwise would hamper his work at the University. Although his research was well recognized by now he did not have a doctor’s degree. The university authorities informed him that such a degree was necessary for him to get full professorship. Therefore, Bose in 1947 submitted his many published papers together with an introduction reviewing his work in multivariate analysis and design of experiments as a doctoral thesis for the degree of D.Litt. Among his “examiners’’ was R.A. Fisher. Bose obtained the D.Litt.

In the spring of 1948, Bose received an offer from the University of North Carolina to accept a full professorship. He also received a similar offer from the University of Illinois. To make his decision more difficult, Raj was also offered two tempting positions in India: the Assistant Directorship of the Institute of Statistics, and the Hardinge Professorship and Head of the Department of Mathematics at the Calcutta University. After a great deal of soul searching, Bose decided to accept the University of North Carolina offer.

Why did Bose decide to move to America? Bose was 48 years old and felt that he had many good years of research left. The two Indian offers would have involved a great deal of administrative work which would have seriously hampered his research efforts. Bose opted for research and joined the University of North Carolina as Professor of Statistics in March 1949. In his own words, “I have never regretted this decision.’’

The 22 years that Bose spent at Chapel Hill were some of the most fruitful and happy years of his life. In April 1950, S.N. Roy, Bose’s former student and best friend, joined the statistics staff at the University of North Carolina. They helped form a small but very gifted and productive Department of Statistics. Like Bose, many of these statisticians later became members of the U.S. National Academy of Science. Had he not died in 1964, Bose firmly believes that Roy would have joined this select membership. As in India, Bose was able to attract excellent students, both American and Indian, to work under him. Many of these prodigies have gone on to distinguished careers throughout the world.

From 1949 through 1954 Bose concentrated on perfecting his design of experiments theories. In 1955, Bose developed an interest in coding theory. Upon investigation, Bose realized that he could apply his factorial design methods to the new theory. This culminated in 1960 in the discovery, in collaboration with his student Ray-Chaudhuri, of the now well-known Bose–Chaudhuri codes; later these codes became known as the BCH codes where H stood for the French mathematician Hocquengham who independently also discovered the codes. For nearly 15 years no better codes were known.

At this time in 1959, Bose, in collaboration with two other mathematicians, made another famous discovery. This was the solution to the two-centuries-old problem proposed by the great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. In 1782, Euler proposed the following conjecture: There does not exist a pair of orthogonal Latin squares of order

n=4k+2 for any positive integer k. Many attempts were made to prove or disprove this conjecture, but it was not until 1959 that Bose, his student S.S. Shrikhande, and E.T. Parker were able to prove the conjecture false.2

Up to 1960, most of Bose’s work had been motivated by applications to statistics and coding theory. His coding theory work had given him a taste of the possible applications of his combinatorics methods. It should be noted that the 1960s saw the blossoming out of the new mathematical area of combinatorics.3 Raj was also doing some interesting work in projective planes with R.H. Bruck, A. Barlotti, and some of his graduate students. In his increasing interest in combinatorial problems, Bose became interested in interconnections between the structure of designs and graph theory. Many of his students have gone on to make major contributions in these four areas that Bose has concentrated on during the past 20 years, these being:

Design of experiments;

Coding theory;

Projective planes; and

Connections between design and graph theories.

From 1966–1971, Bose held the chair of Kenan Professor at the University of North Carolina. In August 1971, Raj retired from the U.N.C. at the age of 70. “Retired’’ is a misnomer as Bose accepted the position of Professor of Mathematics and Statistics of Colorado State University where he remained actively engaged in teaching and research until his second retirement in 1980.

How does one summarize the vast achievements and contributions of such a universal mathematician? Bose has published over 140 papers in a half-dozen different areas of mathematics and statistics. In 1981, his 29th Ph.D. student completed his work. He has given invited talks throughout the world at international meetings and conferences, and been on the editorial boards of five journals. Bose has been the recipient of many rewards and honours. In September 1971, an international symposium on combinatorics was held in Fort Collins in honour of Bose’s 70th birthday. The Association of Indians in America selected Bose as one of the five persons to have received the awards at their first Honor Banquet in 1973. In December 1974, the Indian Statistical Institute gave him an honorary D.Sc. Degree. Bose also served as the President of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics (1971–72). Then in 1976, the United States gave Bose the highest honour that it can bestow on an American scientist by making him a member of its National Academy of Sciences.

While at least in America the “universal’’ mathematician seems to be vanishing, Raj Chandra Bose remains a counter-example. His outstanding career remains for us a standard of what still can be achieved by persons of ability and drive, and a living example of the possible universality of the human mind.

Indranath Sengupta

Bose in Calcutta; 1925–1948

Source : Online portal

(+88) 01920-000502

(+88) 01920-000502 info@biographyavenue.com

info@biographyavenue.com